What could happen if Trump gets US troops kicked out of Iraq?

On Sunday Trump reaffirmed his commitment to withdraw US troops from Syria but insisted he will retain American forces in Iraq in order to "watch Iran."

As The New York Times noted, this single comment "achieved a previously unattainable goal," which was "unity in the Iraqi political establishment" in "a collective rejection of his proposal."

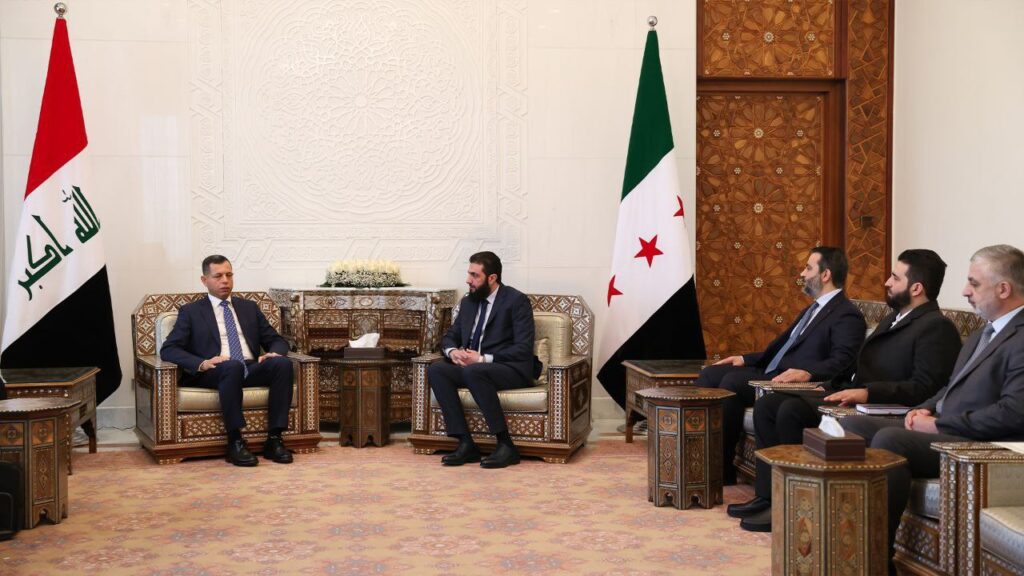

Iraqi Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi reminded Trump that there are no US bases in Iraq and that he will not accept his country being used as a base against any of its neighbours. Iraq's President Barham Salih also said that the Iraqi Constitution prohibits this and expressed his opposition to Trump's intention.

Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the most revered and influential Shiite cleric in Iraq if not among the Shiites the world over, also voiced his opposition to the idea, insisting that Iraq wants "good and balanced relations" with its neighbours and that it "rejects being a launching pad for harming any other country."

Michael Knights, an Iraq expert and Lafer Fellow at The Washington Institute, pointed out that Trump's comment could well jeopardise the future presence of US troops in Iraq since it's the second affront the president made against Baghdad in recent months.

The first was Trump's unannounced three-hour visit to meet American troops at al-Asad Airbase in western Iraq in late December. He met no Iraqi officials during this visit leading to condemnations from Baghdad that his trip constituted a violation of both diplomatic norms and Iraq's sovereignty.

This predictably sparked outrage among Iraqi politicians who support the implementation of legislation to compel the Americans to leave.

A third affront or "a strike three" of a similar nature, Knights told the publication Defense One, then "we're out."

Knights discussed the likely consequences of any US eviction from Iraq with Rudaw English.

Asked what Abdul-Mahdi has to gain or lose, Knights illustrated the fine line the Iraqi leader has to walk.

"Iraq's prime minister knows that US-led coalition support underpins the security gains made since 2014, and so he knows he would gamble with that fragile security," he explained.

"On the other hand, he knows that the heat has to be reduced around this issue before he can work with all his partners to come up with a solution that demonstrates he is standing up for Iraq's sovereignty."

While a US pullout would "not necessarily" affect the NATO mission in Iraq, where alliance member troops are training the Iraqi Security Forces, any imposition by Baghdad of "excessive limits on foreign military presence – which is what Iraqi factions are calling for, not just US – may complicate the NTM-I mission [NATO Training Mission-Iraq]."

Then comes the Kurdistan Region. Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani recently affirmed Erbil's stance that US troops should remain in Iraq while ISIS still poses a threat, arguing that this "is in the best interest of Iraq."

"We believe that until the end of the ISIS threat, coalition forces should stay in this country."

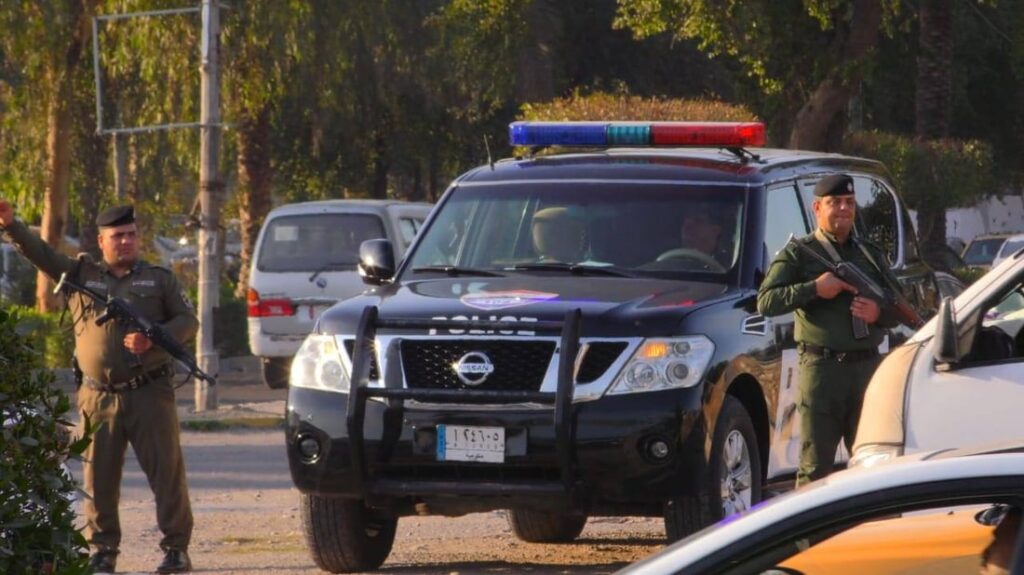

The Kurdistan Regional Security Council (KRSC) has documented an increase in the number and ferocity of ISIS attacks in Kirkuk and Nineveh provinces, among other areas, in recent months.

These attacks are quite lethal and sophisticated, ranging from targeted assassinations of village leaders to use of vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs) and demonstrate that ISIS, while severely weakened, still constitutes a threat to Iraq.

Were Baghdad to evict US troops from the country, it's possible the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) could seek to host at least a residual force of coalition troops in the Region, where those Western troops are also training the Peshmerga.

"The KRG will make its own decisions, but Baghdad would probably expect national compliance," Knights reasoned. "Of course, any Iraqi action may seek to restrict and limit, not remove, foreign forces."

Ultimately, any complete withdrawal of US troops – especially one resembling the 2011 withdrawal, when Washington failed to retain even a residual troop presence – in the near future could fundamentally hinder the wider US-led campaign against ISIS.

"If Coalition forces cannot base in either Iraq or Syria, then the Western involvement in the counter-ISIS fight will effectively collapse," Knights predicted. "Neither Turkey nor Jordan are viable bases, and airspace restrictions might apply to overflights too."

Last April former Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi – upon being asked about rumours that the US had forbidden the Iraqi Air Force from flying over the Hamrin Mountains, which are south of Kirkuk – claimed that "there is a ban on American jets over Iraq."

"Now when they want to fly over Iraq, they need our permission," he said at the time. "Every American military air flight has to get permission from Iraq. Iraqi sovereignty exists over everyone."

Eviction of US troops coupled with any denial of overflight rights could drastically affect the fight against ISIS remnants in Syria.

When Trump announced his intention to withdraw all US troops from Syria last December, the Pentagon scrambled to devise a contingency plan to keep pressure on ISIS there. It hinged on the use of the aforementioned Iraqi al-Asad airbase as a launch pad for US special forces to infiltrate eastern Syria to target ISIS.

If US troops are made to leave Iraq soon because of Trump's actions and the right of overflight becomes problematic for the coalition, then ISIS may get the breathing room it needs to make a bloody resurgence in Syria and possibly Iraq itself.